Now in its third year, Bristol’s Festival of the Future City brings together politicians, writers, artists, scientists, change-makers, academics, journalists, students, the public, economists, futurists, policy makers, roboticists, philosophers, filmmakers, think tanks, charities, social enterprises, city-builders and more, for the largest public debate about the future of cities.

Now in its third year, Bristol’s Festival of the Future City brings together politicians, writers, artists, scientists, change-makers, academics, journalists, students, the public, economists, futurists, policy makers, roboticists, philosophers, filmmakers, think tanks, charities, social enterprises, city-builders and more, for the largest public debate about the future of cities.

This year’s festival (16-18 October 2019) includes a fantastic film programme featuring “classic utopian films about cities; cities in silent cinema; and documentaries on New Towns, democracy, the housing crisis and the anthropocene”. See the full list of films and book tickets here.

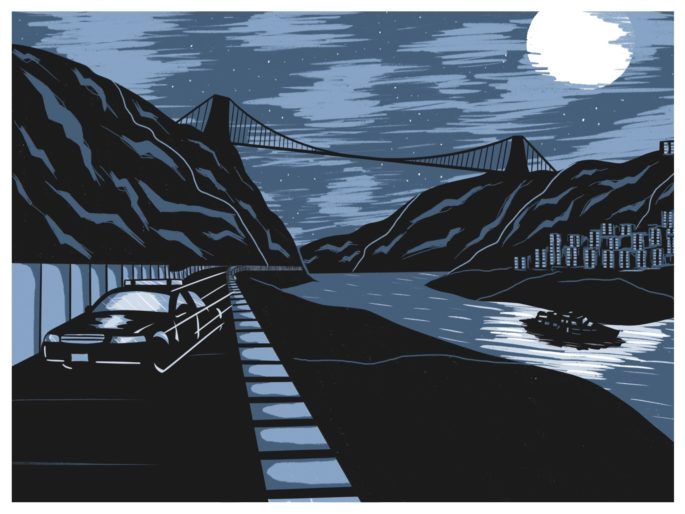

The festival will also feature a season of classic film noirs screening at The Cube, including titles such as The Naked City, The Asphalt Jungle and Kiss Me Deadly. See the full selection of films and book tickets here.

We’re delighted to share the following extract from Mel Kelly’s Film Noir and the City blog, which explores the depiction of the city in film noir, asks what constitutes a film noir and what such films can tell us about urban living.

(Originally posted on the Bristol Festival Ideas website.)

Film Noir and the City

written by Mel Kelly

Film noir: an overview

French critic Nino Frank was among the first to use the term ‘film noir’ to describe a certain style of Hollywood movie. This was in his article ‘Un nouveau genre ‘policier:’ L’aventure criminelle’ (‘A new police genre: the criminal adventure’), which was published in the magazine L’écran français in 1946. ‘Film noir’ became more widely used from the 1970s onwards. It is usually applied to films made in the 1940s and 50s, with later works that replicate or reinterpret some of the noir elements being known as neo-noir.

In Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton’s Panorama du film noir américain 1941–1953 (1955) – the first book to attempt to identify and catalogue film noirs – the authors refer to the difficulty of fixing upon a definition. Most film noirs are crime stories, but they also include gothic romances, heightened melodramas and gritty films addressing social problems. Film noir is not a genre but more of a mood or an atmosphere conveyed through plot, character and visuals.

A film noir may contain some or all of the following:

- A traumatised male protagonist (a demobbed soldier, an aging boxer, a disillusioned crook) undergoing some kind of moral dilemma.

- A world-weary professional investigator (a private eye, a police detective) whose search – often of a missing person – draws him into a disorientating web of deceit that challenges his integrity.

- A femme fatale – beautiful, duplicitous, erotic, amoral – set up as a contrast to a good, homely, supportive female figure and usually punished for her transgressions.

- A crooked politician, a shady DA, a brutal cop and other untrustworthy authority figures.

- A collection of memorable small-part characters: neurotic, wisecracking, grotesque, raddled, deranged, sleazy, eccentric.

- Visually dark, oppressive scenes of high-contrast lighting and deep shadows including the dramatic use of the cage-like stripes created by slatted window blinds.

- Asymmetrical and unbalanced compositions within frames including the use of extreme camera angles and mirrored reflections.

- Labyrinthine plots involving multiple flashbacks, surreal dream sequences (often caused by a blow to the head or the injection of drugs) and unreliable narrators.

- Snatches of snappy, funny dialogue interspersed with eloquent ruminations of jaded cynicism.

- A pessimistic view of humanity and a downbeat ending.

- Among directors associated with American film noir are emigres such as Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Otto Preminger and Robert Siodmark. They brought a European sensibility to their vision of the USA during and after the Second World War, evoking German expressionism, French existentialism and Freudian psychoanalysis.

Many stories were adapted from pulp fiction as well as from more highly regarded hard-boiled crime novels by the likes of James M Cain, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Cornel Woolrich. The photographs of Weegee and the paintings of Edward Hopper are among visual influences drawn from other cultural forms.

The majority of film noirs were originally made as B movies – destined to be the low-budget second feature on a double bill – that only retrospectively gained critical acclaim and the recognition of artistic merit. According to the website American Film Noir, the most prolific of the individual film noir studios between 1940 and 1956 was RKO closely followed by Warner Bros. However, almost 40 per cent of the films were made by independent producers.

Film noir in the city

Most films identified – however loosely – as noir, have a modern urban setting. This is not necessarily a city – it could be a small town – but a large city offers a particularly potent combination of the alienation, paranoia, chaos, fear, corruption, greed, social division and loneliness that lie on the other side of the American dream.

A familiar noir scene takes place on a rain-slicked city street at night. Flickering neon is reflected in oily puddles; the roar of a passing car competes with discordant music blaring through the swinging door of a basement club; and a hunched, trench-coated figure waits in a darkened doorway. The scene might have been shot on location but was more likely to have been filmed on a studio backlot. The constraints of budget and time inspired innovative creative solutions by which to generate the necessary ambiance.

The image of the city in film noir is largely a negative one with a sense that any glamour, excitement or cultural sophistication on offer are for the powerful few. For the protagonist the city is an ambivalent place of menace and mental unravelling.

Among city-themed topics to be addressed in relation to film noir are:

- The architecture of the city – how buildings and interiors shape the narrative and the mood.

- The iconography of the city and its meaning – including the use of signage, lights, fire escapes, hydrants, vending machines, telephone booths and other street furniture.

- The geographic, moral and social divisions of the city – contrasting uptown: downtown; Inner city: suburb; the avenue: the alley; densely packed streets: open-spaces; built-up areas: derelict areas; the land: the waterfront; the luxury penthouse apartment: the seedy rooming house; the high-class restaurant: the diner; the crowd: the individual.

- The sounds of the city.

- Travelling through the city – the automobile and the subway train.

- Comparison of the real city and the city of the imagination: Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York.

- Comparison of the images of the American and of the European city.

- The role of women in the city.

(Continue reading Mel’s blog, which includes examples of film noirs notable for their depiction of a city, here.)